(Shutterstock)

Matt Strauss, McMaster University

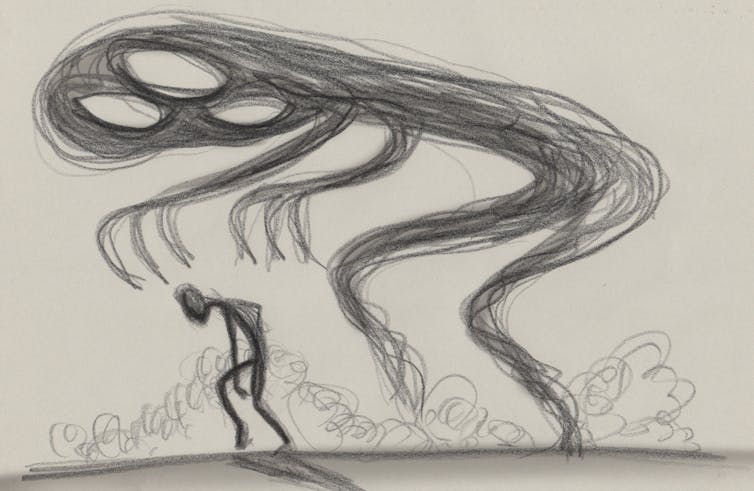

Winter is upon us. And with it comes the annual worsening of depressive symptoms. Sadly, in the United States, suicide continues to claim more lives than firearms, and suicide rates are increasing in nearly all states. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that death by suicide has increased by 30 per cent since 1999 and a similar trend is observed in Canada.

I was distressed but not surprised to learn that these increases occurred over a period of time in which use of antidepressants skyrocketed by 65 per cent. By 2014, around one in eight Americans over the age of 12 reported recent antidepressant use.

I practice critical-care medicine in Guelph, Ontario. Sadly, 10 to 15 per cent of my practice is the resuscitation and life support of suicide and overdose patients.

It is not uncommon for these patients to have overdosed on the very antidepressants they were prescribed to prevent such a desperate act. The failures of antidepressants are a clear and present part of my clinical experience.

Wedded to drugs that barely work

Ten years ago, when finishing medical school, I carefully considered going into psychiatry. Ultimately, I was turned off by my impression that thought leaders in psychiatry were mistakenly wedded to a drug treatment that barely works.

A 2004 review by the Cochrane Foundation found that when compared against an “active” placebo (one that causes side effects similar to antidepressants), antidepressants were statistically of almost undetectable benefit.

Studies that compared antidepressants to “dummy” placebos showed larger but still underwhelming results. On the 52-point Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), patients who took the antidepressants fluoxetine (Prozac) or venlafaxine (Effexor) experienced an average decrease of 11.8 points, whereas those taking the placebo experienced an average decrease of 9.6 points.

(Shutterstock)

I am not suggesting that antidepressants do not work. I am suggesting that they are given a precedence in our thinking about mental health that they do not deserve.

I leave it to readers to look at the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and decide for themselves whether a drop of 2.5 points is worth taking a pill with myriad potential side effects including weight gain, erectile dysfunction and internal bleeding.

It might be, but do note that taking an antidepressant does not seem to decrease the risk of suicide.

Natural therapies that work

The far more exciting and underplayed point, to me, is that multiple non-drug treatments have been shown to be as effective. As a staunch critic of alternative medical regimes such as chiropractic, acupuncture and homeopathy, it surprises me to note that the following “natural” therapies have rigorous, peer-reviewed scientific studies to support their use:

1. Exercise

In 2007, researchers at Duke University Medical Center in North Carolina randomly assigned patients to 30 minutes of walking or jogging three times a week, a commonly prescribed antidepressant (Zoloft), or placebo. Their results? Exercise was more effective than pills!

(Shutterstock)

A 2016 review of all the available studies of exercise for depression confirms it: Exercise is an effective therapy. And it’s free!

2. Bright light therapy

You know how you just feel better after an hour out in the sun? There probably is something to it. Bright light therapy is an effort to duplicate the sun’s cheering effects in a controlled fashion. Typically, patients are asked to sit in front of a “light box” generating 10,000 Lux from 30 to 60 minutes first thing in the morning.

A review of studies using this therapy showed significant effect. The largest study showed a 2.5 point drop on the HDRS, roughly equal to that seen from antidepressants.

The sun gives 100,000 lux on a clear day and I can’t think of a reason why sunlight itself wouldn’t work, weather permitting.

3. Mediterranean diet

This one surprised me when it came out last year. Researchers in Australia randomly assigned depressed patients to receive either nutritional counselling or placebo social support.

(Shutterstock)

The nutritionists recommended a Mediterranean diet, modified to include local unprocessed foods.

Thirty-two per cent of the depressed dieters experienced remission versus eight per cent of those who only received social support, a far larger effect than seen in antidepressant trials.

4. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

This is the best recognized of the “natural” treatments for depression and the evidence is indisputable.

CBT is as effective as antidepressants but more expensive in the short term. However, antidepressants stop working when you stop taking them, whereas the benefits of CBT seem to last.

And as an aside, it is very difficult to overdose fatally on a bottle of therapy.

(Shutterstock)

I freely admit that the trials I have mentioned are smaller than the major antidepressant trials. But whereas antidepressants are projected to bring in almost $17 billion a year for the pharmaceutical industry globally by 2020, the jogging and sunlight industries will never have the resources to fund massive international trials. With this in mind, I am convinced that they are at least as worthwhile as the pills.

Physicians have a responsibility to at least talk to their patients about these options before reaching for the prescription pad.

Dr. Strauss does not recommend changing one’s medication or course of treatment for depression without consulting a physician. If you are feeling suicidal or are concerned about a friend, family member or work colleague, visit www.suicideprevention.ca to find a crisis centre near you.![]()

Matt Strauss, Fellow in Global Journalism, University of Toronto and Assistant Clinical Professor, General Internal Medicine, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.