Treena Orchard, Western University

When love, lust and all things in between come calling, dating apps appear to be the only way to meet new people and experience romance in 2019. They’re not of course, but social media and popular culture inundate us with messages about the importance of these seemingly easy and effective approaches to digital dating. Drawing upon my personal experiences and academic insights about sexuality, gender and power, this article explores what happens when dating apps fail on their promises.

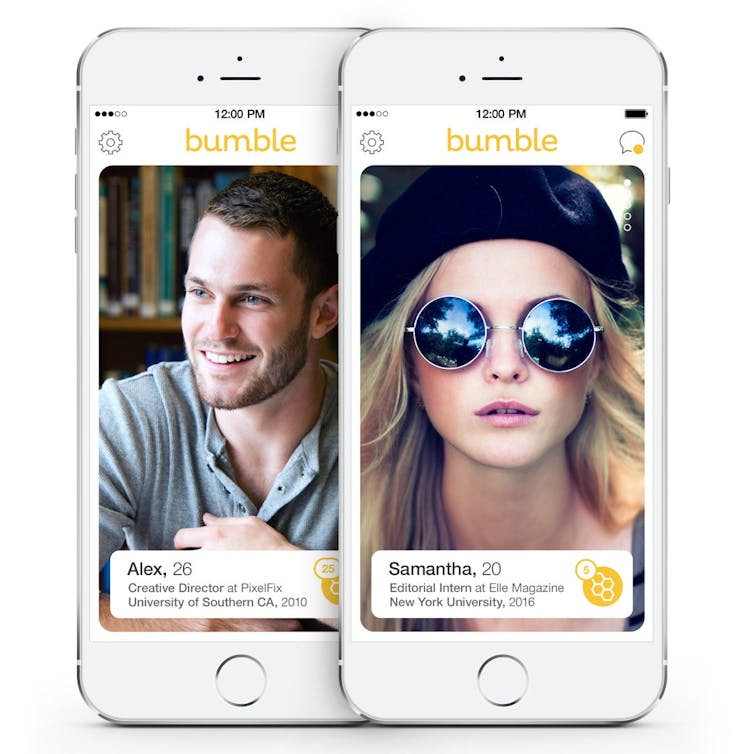

Being a tech Luddite, I never dreamed of using a dating app. However, when other options were exhausted, I found myself selecting photos and summarizing myself in a user profile. I chose Bumble because it was rumoured to have more professional men than other apps and I was intrigued by its signature design where women ask men out. Self described as “100 percent feminist,” Bumble’s unique approach has generated significant social buzz and it has over 50 million users.

As a medical anthropologist, I explore sexuality, gender and health experiences among people in sex work, Indigenous communities and those affected by HIV/AIDS. I had no intention of writing about my socio-sexual experiences, but as soon as I started my Bumble journey the words began to flow. Writing helped me cope with the bizarre things I encountered, and my anthropological insights told me that my observations were unique as well as timely.

But what is Bumble all about? What does it reveal about feminism and gender in contemporary dating culture?

The female worker bee does all the work

Established in 2014, Bumble is branded as a feminist dating app that puts women in the driver’s seat and takes the pressure off men to initiate dating conversations. In a 2015 Esquire interview, Bumble CEO and co-founder Whitney Wolfe Herd explained the honeybee inspiration:

“Bee society where there’s a queen bee, the woman is in charge, and it’s a really respectful community. It’s all about the queen bee and everyone working together. It was very serendipitous.”

However, a honeybee hive is less about sisterhood and more about gendered inequity. Just as female worker bees do the heavy lifting as they care for larvae and their hexagon lair, Bumble women perform the initial dating labour by extending invitation after invitation to potential matches. Bumble men, much like male bees, largely sit and wait for their invites to come.

Courtesy of Bumble

In my five months on Bumble, I created 113 unique opening lines, each of which involved not just work but also a leap of faith. Here’s just two examples:

Hi X! I like your photos, they’re attractive and interesting. You’re a personal trainer, it must be rewarding to work with people to achieve their goals …

Hey, X. Your photos are hot …want to connect?

Will he respond? Will this one like me? Putting myself out there repeatedly made me feel vulnerable, not empowered.

Sure, there was some short-lived excitement, but much of my time was spent wondering if they would respond. Only 60 per cent of my opening lines were answered and I met just ten men in five months, which is a nine per cent “success” rate.

Of my 10 encounters, four rated as very good to excellent, three as quite bad and three fluctuated in the middle: not terrible, but not something I’m keen to repeat. Like the attractive guy with the prickly arms (because he shaved them) who twirled me around in my dining room but could barely tie his shoes up because his pants were so tight. Or, the guy who talked obsessively about being 5’6″ but really, really wasn’t.

A girl-power bubble

My digital dating journey was not the effective, empowering experience I hoped for. The discrepancy between Bumble’s sunny narrative and my stormier encounters stemmed from the app’s outdated brand of feminism. The women-taking-charge-for-themselves model assumes that we live in a girl-power bubble. It ignores men’s feelings about adopting a more passive dating role. This creates tensions between users. I learned the hard way that despite our feminist advances, many men are still not comfortable waiting to be asked out.

Some Bumble men view the app’s signature design as a way for women to rob them of their rightful dating power. Many openly critiqued us for acting “like men” and I was ghosted, sexually degraded and subjected to violent language by men who resented me or what I represented as a feminist. This was confirmed by several of my matches, who discussed women’s acquisition of socio-economic and sexual power as a problem. These insights not only shocked me; they impaired my ability to have meaningful dating experiences on Bumble.

The #MeToo and Time’s Up movements continue to illuminate how much unfinished business we have ahead of us before gender equity is a reality. My Bumble experiences reflect the same unfortunate truth, as do other studies about the complex relationship between gender and power relations on dating apps.

Using a feminist dating app in a patriarchal world is messy, but also fascinating for what it reveals about sexuality, gender and power in the digital dating universe. Bumble needs a serious upgrade it if truly wants to empower women and make room for men en route to more meaningful dating experiences.

One suggestion would be to remove the “she asks” and “he waits” design so both partners can access one another as soon as a match is made. Bumble might also consider having users answer questions about gender equity and feminism before matches are generated. This could make digital dating experiences less of a bell jar and more of an equitable mess.

Another idea is to have Bumble refresh its narrative to support women’s desires and to help diverse dating roles be more readily accepted by men. The app could add a forum where users can share their various Bumble experiences in ways that encourage safe, engaged dating-related communication.

My personal feeling is that instead of depending exclusively on dating apps, it’s best to use multiple dating methods. This means having the courage to act on our desires as they surface in the grocery story, the art gallery, or at the subway stop. It can be terrifying but also much more exciting than swiping right. Go for it!

[ You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter. ]![]()

Treena Orchard, Associate Professor, School of Health Studies, Western University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.